Developing student-led mission statements and a culture covering stories that matter can serve both school and local communities.

Many years ago, I was confronted by an angry parent after a long production meeting. She felt her daughter, an editor, spent too much time working on the paper. “This isn’t the New York Times!” she reminded me.

I told her the commitment to publishing a successful student publication can be similar to playing a sport.

I don’t think my response satisfied her, but her outburst got me thinking about the similarities and differences between professional and student publications: How do their missions and purposes compare? How do publications work to support their mission statement? How do we encourage students to live up to the publication’s mission? How can student journalists best serve their communities?

How do their missions and purposes compare?

According to their website, The New York Times “mission and values guide the work [they] do every day.” Their mission statement identifies how they serve their readers and society as a whole:

We seek the truth and help people understand the world.

This mission is rooted in our belief that great journalism has the power to make each reader’s life richer and more fulfilling and all of society stronger and more just.

How can student editors use this model to guide what they do? John Bowen wrote a series of blog posts on creating a mission statement back in 2015. It was published in four parts and included a wealth of resources and guidelines, including ethics, rights and responsibilities. It’s well worth revisiting. Here are the links:

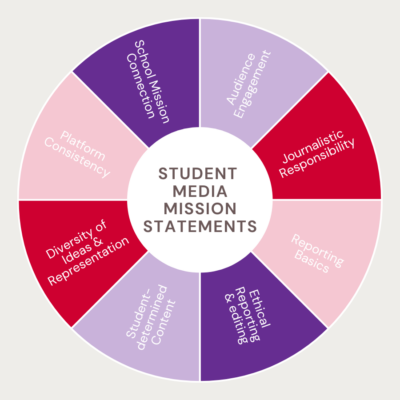

Infographic created by Morgan Bricker using Canva with information adapted from “Careful preparation creates strong mission statements” part two of a series on pieces of the journalism puzzle: Mission Statements by Candace and John Bowen.

Part 1: Build a strong foundation

Part 2: Careful preparation creates strong mission statements

Part 3: Points to avoid in mission statements

Part 4: Fitting the pieces into a strong foundation

For this discussion, I want to focus on one part of the model mission statement provided: “Student-determined expression promotes democratic citizenship through public engagement diverse in both ideas and representation.” Borrowing from both mission statements, how do we create journalism programs that “promote democratic citizenship” and make each reader’s life richer and more fulfilling, and all of [the school community] stronger and more just”?

How do publications work to support their mission statement?

Michael Lozano believes that students must design the publication’s mission statement. He is the Youth Journalism Initiative Manager for Cal Matters and has worked with student journalists for the last 12 years. CalMatters is a nonprofit news organization covering California. The Youth Initiative works with student journalists and helps “teachers and community leaders ready more high school and middle school students for a career in journalism.”

He has found that engaging students in developing their mission statement brings out issues they believe are important to them and their readers.

“They talked about the bikeability of their neighborhoods, pollution and community issues,” he said. “But they also highlighted a lot of young people of color. They wanted to see stories that uplift their communities. Including this in the mission, in the model, is also a way of boosting engagement.”

School districts are small communities with government officials (school board members, administrators) and constituents (students, parents, staff, and taxpayers). Student publications can play an essential role in helping readers better understand the power structure and decision-making process involved in school communities. This should be reflected in the publication’s mission statement.

Meeting this mission isn’t easy. Student editors and advisers need to dedicate time, effort and space to serving their audience in this way. They must develop journalistic relationships with school and student leaders and attend board meetings. If board members and administrators are genuinely interested in promoting democratic citizenship, they will assist student journalists in this mission to create transparency for the school community. Student journalists can also assuage administrators’ fears by publishing the mission statement and the journalistic rights, ethics and responsibilities that guide them.

How do we encourage students to live up to the publication’s mission?

It really comes down to developing a culture in which student leaders focus on the mission and encourage the staff to cover important issues.

This can take time.

Michael Simons is the adviser of The Tesserae – the yearbook of Corning-Painted Post High School in New York. He was also named JEA’s H.L. Hall National Yearbook Advisor of the Year in 2021. He knows about developing a culture where students challenge themselves to produce content that matters.

“I think advisers need to play the long game,” he said. “Incremental change, gradual progress — things can scale over time both in terms of significance.”

Simons suggested starting by localizing regional, national and international news to break the ice. This can lead to conversations about big topics within the school.

He provided an example for exploring the topic of mental health by looking at where it’s already being discussed in school.

“Maybe the health teacher does a unit where kids inventory their positive coping mechanisms,” he said. “And a yearbook staff puts together a “DOs” & “DON’Ts” list of handling exam stress or anxiety by offering five tips from that health teacher, and a quote from a kid about how they settle their nerves around exams, or how they decompress and cope when feeling anxious.”

This approach can also help guard against administrators worrying about students writing about mental health by using adult experts in the school and providing coping strategies rather than focusing on teen struggles.

“Before you know it, kids could be running a full-spread feature on concussions, or mental health, or positive dating relationships,” he said. “Because…well, that’s what we’ve always done. We always tell big stories. Because they’re OUR stories, and we’re the ones best equipped to tell them.”

Of course, models of this type of work – scholastic and professional – can inspire student journalists.

On Oct. 28, Simons presented examples of “big stories” in his Keynote Speech at the Garden State Scholastic Press Association’s Fall Press Day at Rutgers University. He shared a scholastic news story that gained national coverage.

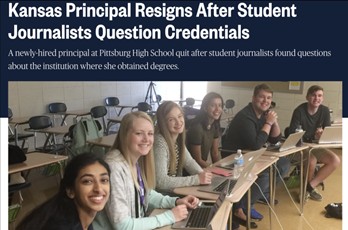

The Booster Redux, the student newspaper of Pittsburgh High School in Kansas, found that the resume of the recently hired principal contained discrepancies. It turned out that she didn’t attend a university listed. Their reporting led to the job offer being rescinded. The staff who worked on this story became known as “the Pitt 6,” and national outlets picked up the story.

Simons cautioned the more than 300 students in the room.

“I’m not saying to wake up and say, “Oh, I’m a student journalist. Who should I expose today?”’

He went on to highlight the importance of human interest stories like The Lion’s Roar Yearbook spread on the support the school community gave to a terminally ill teacher.

Simons encouraged students to use their First Amendment rights to shine a light to effect change in their communities for the right reasons. He said doing so is extremely powerful.

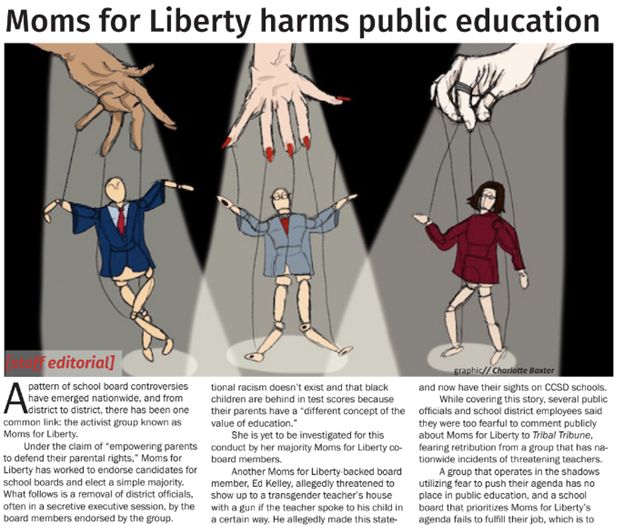

His presentation included student newspapers and yearbooks that covered serious issues impacting their schools and communities, including race, mental health, hazing, sexual assault, immigration, and politics influencing school board decisions.

How can student journalists best serve the community?

In this way, students play a similar role as professional journalists. And with the need for more local news coverage in many areas, they can fill that void.

In New Jersey, student journalists publish content through the TAPinto network of community news sites. The Highlander, Governor Livingston High School’s student newspaper, publishes all of its content on the Berkeley Heights TAPinto site.

Increasingly, high school and college students are providing news to local communities that traditional media outlets are not serving. Candace Bowen’s four-part blog post on student journalists in news deserts was published on the JEASPRC site last year. It’s definitely worth revisiting.

These issues were also addressed in sessions at JEA’s Fall Conference in Philadelphia in Nov. 2024:

- Reporting and Publishing Beyond Your Campus with Ed Madison from the University of Oregon, Michael A. Spikes from Medill, Candace Perkins Bowen, SPLC Executive Director Gary Green

- Covering School News for Your Community with Candace and John Bowen

- Covering the School Board with Jay Goldman from the American Association of School Administrators

Journalism advisers and students can also stay tuned to the JEA/NSPA Spring 2025 National High School Journalism Convention site for opportunities to learn more in the future.

Chatwan Mongkol is the founder and editor of The Nutgraf, a weekly newsletter about student journalism published on Substack. He recognizes the power high school journalists have.

“Being in a high school newspaper usually gives you a unique knowledge of the happenings inside your district,” he said.

A Nutgraf profile of New Jersey’s High School Student Journalist of the Year Gia Gupta provides a glimpse of the impact covering big stories can have. Gupta was the Editor in Chief of The Eastside – Cherry Hill East High School’s student newspaper.

Gupta discussed a story The Eastside did on student experiences with discrimination in school.

“It wasn’t just believing in myself,” she told the Nutgraf. “More like knowing that what I was doing was making a difference and that I could contribute to something meaningful that was so important. It was the general scheme of feeling like this work was actually making a difference.”

In The Nutgraf, Mongkol highlights the efforts of student journalists and the critical role they play.

“Follow what your education board is talking about, especially if you’re in a news-deserted area where no other outlet reports on every meeting,” he said. “Most of the time, it’s the parents that voice their concerns to the board; reporting on what happens there could encourage students to share their thoughts as well.”

Written By: Tom McHale